{Lying awake one night Lucy wondered what Charles thought about when he lay awake. Did he have nightmares? Did he remember that blank sheet of paper signed with his name? Nothing, it would seem, had been written on it. That act of courage had been in vain. Nevertheless he had sent the paper. He had done it.

And did he think of the great Earl of Strafford, the scapegoat who had not saved his king after all? He had laid down his life for him but it had been in vain. All in the end had been failure. Nevertheless he had laid down his life. He had done it.

(Suddenly she heard Old Sage’s voice:)

"The words 'in vain' are not known to us here. Nor is failure, nor success. But the life laid down is known to us. And love in its true profundity is known. And the maintaining of faith is known. These are for us the sun and moon and stars.”}

Elizabeth Goudge, The Child from the Sea, book III, chapter 5

During the tumultuous years of the English Civil War (1642-1651), towns, families and indeed Britain itself was torn apart. We get a taste of this in Goudge’s last novel, The Child from the Sea. So many historical events and figures are woven into Goudge’s tale that at times it is hard to keep track them all if you are not a British historian. But even if you are not a historian, Goudge strings some together to help us find the relevant comparisons and contrasts.

The concept of the scapegoat is one of the most compelling parts of this novel, and Goudge has many real, historical events to chose from to set up this theme. The quote above focuses on two instances: Charles II offering a blank signed paper for his enemies to write on it whatever terms they wished in exchange for his father’s life, and the death of the Earl of Strafford, friend of Charles I. It is here in these terrible circumstances that Goudge wishes to remind us of a heavenly perspective. She uses Old Sage to point out that these seemingly unsuccessful offerings by Charles and the Earl are not, as Lucy thinks, worthless. Goudge speaks through Old Sage, from beyond the grave, to share the hope that we all need about the next life in heaven: “The words ‘in vain’ are not known to us here.”

The Life of Exiles

The wandering life of exile is another theme that pops up often in Goudge’s 20th century novels. A few of them are pictured at the top in our Read-Along list for the year. We read The Castle on the Hill earlier this year on Instagram, and Mr Isaacson’s life of exile during WWII makes up a large part of the novel. His violin plays tunes of wandering, until he finds a home. Goudge’s book about St Francis, My God and My All, is definitely a book about Francis’ wanderings as he looked to share the love of God all over his country. And even Henrietta’s House is a fairytale about uncomfortable wanderings that takes you eventually to a warm and cozy home.

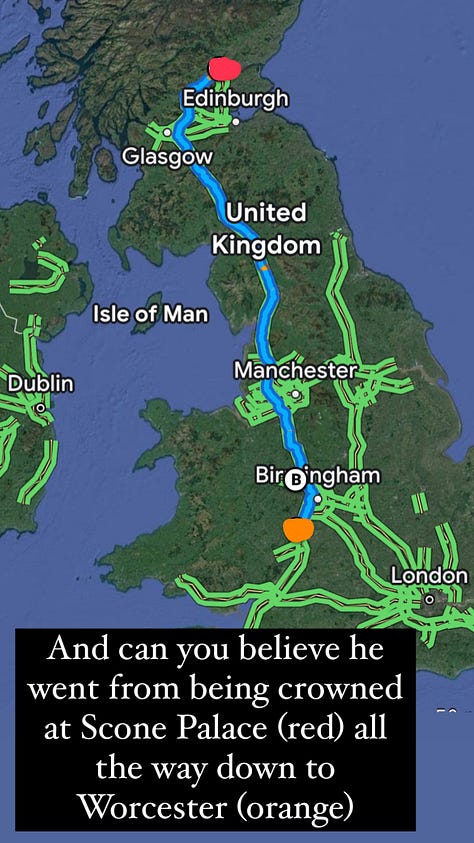

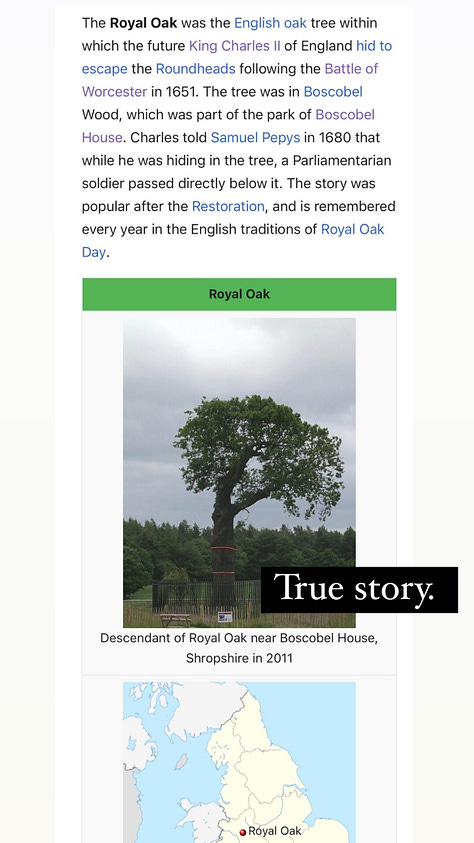

Charles II and his most loyal men took an extra trip in the middle of the continental wanderings: to Scotland to begin a march on London. But he never made it, as disaster befell the Royalist at the battle of Worcester.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Elizabeth Goudge Bookclub’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.